Being a Black preacher in the post-civil rights era can be very costly. From the fiery, prophetic voice of the Rev. Dr. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr., pastor emeritus of famed Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, to the unrepentant militancy of Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam, clergy in the tradition of Black liberation theology find themselves in the cross-hairs of media pundits and across the line from many popular Black mega-church pastors.

Wright gained greater prominence in 2008 as his most nationally recognized congregant, then-U.S. Sen. Barack Obama, launched his campaign for president of the United States of America.

Members of the media delved into Pastor Wright’s ministerial background, unfurled snippets of his sermons and widely broadcast 10- and 15-second sound bites that were manipulated to portray him as a hate-monger and an unpatriotic, “God damn America” preacher.

The media-controlled interpretations of Wright’s theological perspective created such a furor, presidential candidate Obama publicly severed the 20-year relationship with his pastor. Wright’s consistent sermons based on Black liberation theology preached from his Chicago Southside pulpit fueled the attacks against him.

Twenty-four years earlier in 1984, Minister Farrakhan experienced similar treatment, after the Rev. Jesse Jackson announced his candidacy for president. Minister Farrakhan, the head of the Nation of Islam, was accused of being anti-Semitic, because he criticized religious people who failed to live up to the tenets of their faiths including Christians, Muslims and Jews.

Media personalities edited Minister Farrakhan’s messages to short clips and disseminated them as actual statements without either context or further reference. His words were reduced to single sentences, although the length of his Black liberation orations usually exceeded an hour.

On the other hand, less traditional Black preachers who spew a gospel of prosperity, feel-good-about-yourself theology, and keep-the-people-entertained doctrine found their soft-pedaled messages attracted churchgoers without too much distraction.

“Members of the Black Church are flocking to ‘religious’ leaders who are totally out of touch with the liberation agenda and who are wholeheartedly preaching greed as the ‘new level’ of spirituality to which they have transitioned,” says the Rev. Dr. J. Alfred Smith Jr., pastor of Allen Temple Baptist Church in Oakland, Calif.

Theology professor Dwight N. Hopkins of the University of Chicago Divinity School, named some celebrity preachers whose non-traditional Black religious approach won favor with former President George W. Bush.

“You’ve got Creflo Dollar, Eddie Long, T.D. Jakes, and there are about two others,” Dr. Hopkins told BeliefNet, the online religious source. “They’ve had access to President Bush, and he’s actually promoted them. I’m not saying it’s good or bad. I’m just saying they have similar theologies that have political consequences with the president.”

Smith is less opaque in his criticism of Black preachers, who have found salvation through money collection and prosperity promotion. In a sermon delivered at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Los Angeles last year, Smith decried the absence of prophetic sermons in exchange for easy listening, soul stirring rhetoric.

“What is going on in the Black church with 50,000 believers gathering to get high spiritually is comparable to 80,000 Blacks gathering to hear Nelly or 50 Cent,” he warned. “Between Nelly and Negro preachers, between Dollar and 50 Cent, the Black church in North America is on the verge of a breakdown.”

Professor Hopkins agrees and adds, “America sees that and thinks ‘We thought that was the Black church.’ Prosperity gospel is a recent development, but the whole personal salvation and social justice has been there since the Black church began.”

Smith chided, “Black parishioners are interested in large gatherings of praise where Darfur, Sudan, Angola, the Congo, and Colombia never get mentioned. (They) are interested in large gatherings of praise where they can gather for an entire week of getting their praise on and getting their shout on, speaking in tongues and spending their dollars.”

A national conference of Black clergy convened in Los Angeles in 2005, where conveners were urged to stand against popular culture, secularism and violence. The African American Church Strategy Team, a coalition of eight Black Presbyterian churches, brought together 121 preachers and lay Christian leaders from 10 states. The theme of the four-day gathering was “Reflecting Scripture in a Post-Civil Rights Era: Declaring Our Lord Jesus from the Pulpit, in the Pew, on the Pavement.”

The Rev. Dr. Cecil “Chip” Murray, a senior fellow of the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the USC and the former pastor of First A.M.E. Church in Los Angeles, takes exception to the term “post civil rights” in his criticism of what has happened in many Black churches.

“Today we hear talk of the post civil rights era and that is precisely a problem we meet with the so-called post civil rights church,” he says. “When you speak of Black clergy now, you are speaking of a large percentage who have yielded to materialism,” Murray complains. “They have yielded to consumerism. They have yielded to ‘me too-ism’ just going to preach and work people’s emotions up and then say, “I’ll see you next Sunday,” and those people walk out to go through hell.”

The Rev. Dr. Cain Hope Felder, professor of biblical languages and literature at Howard University School of Divinity in Washington, D.C., staunchly criticizes secular Christianity. He told the Los Angeles Times six years ago, “Too many preachers have become so enamored with fame, money, large congregations and the art of preaching as entertainment that they have forgotten their calling.”

At the Claremont School of Theology, Murray instructed students preparing to serve Black churches, “I define Black preaching as liberation preaching: ‘I have come to set the captives free’. It isn’t the elevator of social acceptance that sets us free. It isn’t the occasional flashbulb that goes off in your face. It is the understanding that I have been sent to set free the captive: the captive mind, heart, and spirit.”

Despite criticism about the shifting emphasis from liberation preaching to enriching preachers’ pocketbooks, Black clergy continue to retain high regard within the African American community. But, there are cautions that respect may be eroding.

The Rev. Dr. C. Dennis Williams, pastor of Brookins Community African Methodist Epsicopal Church in Los Angeles, is concerned about behaviors of some high-profile preachers which placed them in a negative public light.

“Many of us have been plagued by scandal and character flaws which have forfeited efforts and cast a cloud of distrust within the community,” said Williams. “Our respect level as African American leaders has lost a tremendous amount of momentum.”

Murray has a prescription to change course and correct the direction many preachers are headed.

“We are going to need a certain percentage of churches to coalesce. If we can just get a consortium of churches that say, ‘we must reconstruct the church, we must reinvent the church, we must re-empower the church,’ then we can go on with economics, education, imaging, family and all because we will have a format that we need in the 21st century.”

“Let us reclaim our prophetic voice,” Oakland’s Smith preached at Bethel A.M.E. on Jan. 31, 2010, “and address the fact that more African American males in California enter our prison system on a weekly basis than the number of African American males who enter U.C. Berkeley on a yearly basis. Fifty times more African Americans enter our prison system than our leading universities.”

In Detroit, Mich., the Rev. Dr. Kevin M. Turman, pastor of Second Baptist Church, sees hope for Black churches to redeem significant standing in African American communities. He contends, “The church, its values, its vision and its priorities are consistently countercultural, especially in capitalist, self-centered, immediate-gratification-oriented times such as these.”

Celebrating his church’s 175th anniversary, Turman says efforts to gain greater attention are countered by competing forces beyond the control of most Black preachers.

“What is new is that our congregations and communities share the ‘moral microphone’ with so many other voices. The Internet has opened a world of possibilities for influencing the perspectives of members and interested parties on what the Bible means and how to apply its teaching,” Turman explains. “In many ways, the adversary of clergy, in particular, and the church, in general, is always the tide of contemporary culture.”

Turman confesses, “Cultural conservatism means that unless the congregation understands the issue, many pastors are hesitant to get too far out front on the matter. We cannot always be sure what ‘thus says the Lord’ on some of these issues and the lack of clarity has an effect on fervor.”

Black preachers are challenged to resist temptations of popular trends that gravitate toward mega-church attractions at the expense of pressing issues affecting Black people. There is no shortage of desperate conditions among African Americans that require the attention of the Black church.

In Los Angeles, Williams says, “The main issue that affects the Black community from my perspective is HIV/AIDS, homelessness, and drugs.” He cites, “All three of them have a certain correlation. The church is silent on them, but could be a stellar voice in the community and bring about change if we only move beyond the walls of the church.”

Some changes taking place in many churches Turman believes are not helpful to meet people’s needs. “What is new is that the rise and profitability of spiritual music has surpassed the role and impact of Gospel music, rendering the melody and music often more important than the message.”

Black churches are facing are other troubles as well. Turman contends, “They are being depleted of role models, leaders, officers and income needed to provide the breadth and depth of ministry our broader community sorely needs.”

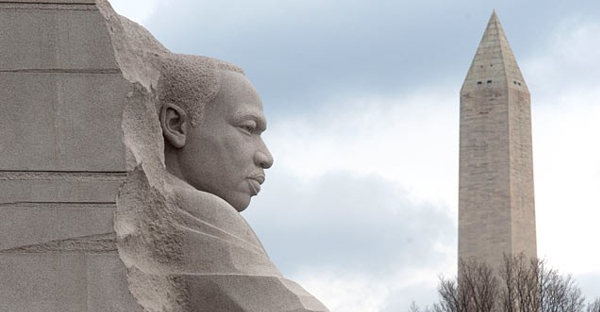

Looking back, Murray remembers, “During the civil rights renaissance and revolution, the church exercised leadership such as Martin Luther King, Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young and others coming out of the Black church.”

Murray indicates a false sense of accomplishment may contribute to what appears to be a leadership gap in Black churches. “When you talk about post civil rights, then you are acting as if we have arrived, when we have not arrived. Yes, there is someone who looks like us in the White House. Yes, slave labor built the foundations of the White House, but under no circumstances does that mean the manifold problems are solved.”

“With the advent of Dr. Martin Luther King as a preacher and leader,” says Dr. Williams, “many Black preachers received their call to the ministry during that time and wanted to imitate his leadership and oratorical skills. The Civil Rights Movement gave them the opportunity they needed to do that.”

The inspirational sermons of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that motivated the cadre of Black preachers who surrounded him along with “church-going, kitchen-working, and basement-praying women” to elevate the Civil Rights Movement, no longer have the power or appeal to capture media attention.

Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington and “The Mountain Top,” his last sermon on the eve of his assassination in Memphis, Tenn., in 1968, fill airwaves during commemorations of his birthday and memorial.

His strident calls for nonviolent, direct action have waned in the wave of mushy messages to advance privatization and personal profits. As a result, Black liberation clergy face the daunting demand to demonstrate a relevant, upbeat presence in society.

“This is for a number of reasons. Racism, segregation, lynching and the bombing of churches and buses were and remain clear and clearly understood moral and theological matters,” Turman says.

“Immigration reform, securing regional equity, rights of the mother versus rights of the fetus, bailing out the banks versus bailing out the car companies,” Turman continues, “the rate and necessity of government spending versus the size of government debt along with so many other issues, can be more challenging to understand and for which to find a clear moral or theological handle.”

“Our challenges are much more extensive and broad now,” as Williams sees it. “We are not contending with just issues of race, and discrimination. We have (an) other onus to deal with such as cyberspace demons on the Internet that appeal to our young African American genre. The infusion of fast food restaurants that are replete in our communities moreso than any other area, which then cause our African American youth to grow up with health issues such as obesity and diabetes.”

Prioritizing the urgency exemplifies the difficulty Black preachers have to deal with daily. Turman begins by saying, “While access to quality healthcare, obtaining quality employment in a changing economy and the deterioration of family and neighborhoods all vie for a close second, I believe that access to quality public education is the most critical issue we face.

“There is a reason that it was against the law to teach slaves to read,” he continues. “There is a reason that access to schools was segregated. There is a reason that equal funding for public education regardless of school systems remains an unmet social challenge.”

He argues, “The opened and enlightened mind is an instrument, a tool, a gift that keeps on giving.

Too many of the bright minds of our communities are drying up like raisins in the sun. The ensuring of access to and opportunity for quality public education has been so removed from local jurisdictions that local pastors, educators, administrators, parents and community activists cannot help but be frustrated in our efforts to affect the substandard status quo.

“But we must, in Bible study, pulpit and community settings remain true to our calling. We may not be able to win the battle by ourselves, but we can still call out and point to the promised land,” Turman surmises.

The long litany of contemporary issues across the United States requires a greater reach for ministers to keep their sermons focused on cutting-edge challenges without compromise. They are expected to do more than preach. They must live their sermons and enter the social fray in the streets where people too often die prematurely. Moving from the sanctuary into the streets allows churchgoers “to pray with their feet,” as Rabbi Abraham Hershel explained while marching with Dr. King through Selma, Ala.

The plethora of critical concerns forming into crises has plunged Black families and individuals into the depths of depression, both mentally and financially. Spiritual support to sustain them through prolonged periods of deprivation has been short-changed in part by too many Black clergy turning away from the power of prophetic preaching.

“You’ve got the preachers who say we are here for getting you into heaven,” reminds Dr. Murray, “but the church exists for more than getting you into heaven. It exists also for getting you out of hell, and for getting the hell out of you, and that is where we are going to have to reinvent ourselves. We are going to be in hell, because we are no longer a predominant minority in the consciousness of a majority that says, ‘we don’t want to hear you folks crying no more. Look at the White House’.”

February 25, 1964 was supposed to be a great day for boxing fans. It was the day a loudmouth, 22-year-old fighter named Cassius Clay was finally supposed to have his bragging stopped by fearsome heavyweight champ Sonny Liston. That was not to be, and after the young Clay’s shocking victory, there was no celebration planned, since no one thought he would actually win. No one except his three friends, activist Malcolm X, singer Sam Cooke and football player Jim Brown. The foursome threw together a party in Malcolm’s tiny hotel room in Overtown, the city’s downtrodden black ghetto. The next morning, Cassius would make an announcement that would shock the world yet again. One Night in Miami… imagines what might have transpired on that very real, very fateful night in Malcolm’s motel room in 1964. The civil rights struggle was ready to boil over. And in less than a year, two of these friends would be dead. But on this night, the possibilities seemed endless.

February 25, 1964 was supposed to be a great day for boxing fans. It was the day a loudmouth, 22-year-old fighter named Cassius Clay was finally supposed to have his bragging stopped by fearsome heavyweight champ Sonny Liston. That was not to be, and after the young Clay’s shocking victory, there was no celebration planned, since no one thought he would actually win. No one except his three friends, activist Malcolm X, singer Sam Cooke and football player Jim Brown. The foursome threw together a party in Malcolm’s tiny hotel room in Overtown, the city’s downtrodden black ghetto. The next morning, Cassius would make an announcement that would shock the world yet again. One Night in Miami… imagines what might have transpired on that very real, very fateful night in Malcolm’s motel room in 1964. The civil rights struggle was ready to boil over. And in less than a year, two of these friends would be dead. But on this night, the possibilities seemed endless.