The health of nations is more important than the wealth of nations. – Will Durant

The health of nations is more important than the wealth of nations. – Will Durant

The idea that someone else will care for you, your family, or your community better than you seems to be the purveying attitude of African America in almost every facet of our strategy today. This is of course assuming you believe we have an institutional strategy of our own to begin with. Instead of building and competing for power and control we seem content on waiting for others to share their spoils with us because it is the “right” thing to do only to be “shocked” when others idea of right and our idea of right do not acquiesce.

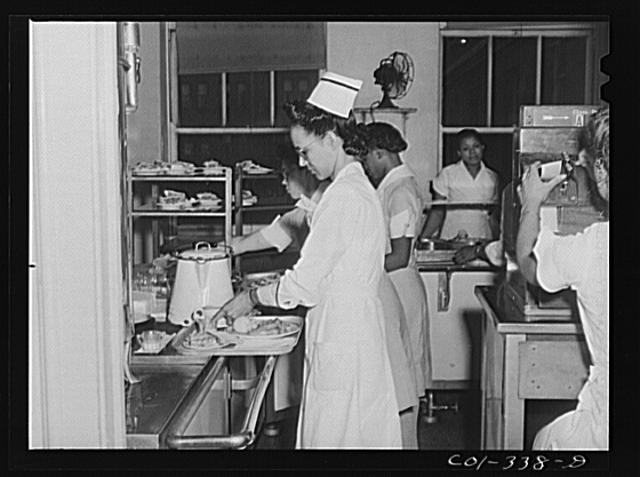

The history of African America and health has always been a precarious one. A people descended from the medical genius, Imhotep, known as the “father of medicine” who performed the earliest known surgery to the inspiring story of Dr. Ben Carson in present times. Healing sanctuaries and temples to the goddess Sekhmet are known to be the earliest “hospitals” to date. Fast forward a few thousand years to America and African Americans in Detroit alone owned and operated 18 hospitals of their own between 1917 to 1991. The confines within their own hospitals and medical ecosystem would seemingly be the only place where safety existed. From colonial times to present time, as noted in Medical Apartheid by Harriet Washington, when African Americans went outside of their own medical ecosystem we were and are subject to some of the most brutal medical experiments and abuses known in medical history. In an interview with Democracy Now, Ms. Washington is quoted giving examples of these abuses from past to present, “James Marion Sims was a very important surgeon from Alabama, and all of his medical experimentation took place with slaves. He took the skulls of young children, young black children — only black children — and he opened their heads and moved around the bones of the skull to see what would happen. He bought, or otherwise acquired, a group of black women who he housed in a laboratory, and over the period of five years and approximately forty surgeries on one slave alone, he sought to cure a devastating complication of childbirth called vesicovaginal fistula.” Ironically, as it were, Dr. Sims would go on to become president of the American Medical Association. Ms. Washington then goes on to present times stating “It’s black boys who have been singled out for these very dangerous experiments, such as a fenfluramine experiment that took place right here in New York City between 1992 and 1997. A lot of the abuse in African Americans has dissipated, but that kind of research is being conducted in Africa, where the people are in the same situation. They don’t have rights. They don’t have access to medical care otherwise, and Africa is being treated as a laboratory for the West by Western researchers.” Despite this obvious and consistent pattern of behavior we continue to seek to dismantle our own medical ecosystem.

It is no secret that the health of the African American community has always been in peril. Arguably today, more so than it has ever been in our history in this country. To some, the issues of medicine are a one size fits all prescription for any human anywhere. It is true we all have the same anatomy certainly but historical diet from our ancestry, environment, stress from the Middle Passage, slavery, and socioeconomic burdens that culminated after desegregation have taken its toll and many other factors create unique factors in the African American health dynamic. In fact, every group based on their historical geography and diet has unique health features in their present health makeup. As such what is conducive to one group will not necessarily work for another. The variables at play do not provide for blanket medical solutions or care. Biological diversity exist in every species be it cats (lions, cheetahs, tigers) or humans. Yet, our desire to ignore these realities for the sake of creating a racial or ancestral Utopia has created a boom in our health risk with no seemingly end in sight. The numbers bear out a bleak picture of African American health today. African American life expectancy is 4.3 years less than the average American and 4.8 years less than European Americans. We currently have the highest age-adjusted death rate among all populations. The infant mortality rate in America for all is 6.8 per 1000 births yet for African America it is 13.2 per 1000 births. Approximately 20 percent of all African Americans are uninsured versus a national average of 15.9 percent. We are going extinct and do not even realize it.

Nathaniel Wesley Jr.’s book “Black Hospitals in America: History, Contributions and Demise” points out that at our apex there were 500 African American owned and controlled hospitals. Today, Howard University in Washington D.C. is the last one standing. In 1983 as Dillard University was selling its hospital Flint-Goodridge their president at the time, Dr. Samuel Dubois Cook stated that its demise was a result of “tragic mismanagement, social change that desegregated hospitals, financial irregularities, the fact that 90 percent of the patients were on Medicare or Medicaid and the loss of broad community support”. It would be hard not to assume that these were the underlying cause of the majority of most African American owned hospitals since as we know fervently believe that our proverbial ice could not possibly be as cold as the ice in other communities.

Rethinking the role of hospitals in general is needed given the rapid rise of healthcare cost but especially so in the African American community where the ability to afford private healthcare is almost impossible given our lack of wealth. While Asian and European America’s median net worth both approach $100,000 the African American median net worth is close to $2,000 and dropping according to the Economic Policy institute. Hospitals in our communities should be fashioned as health and wellness focused on preventive care, nutrition, and alternative medicines more unique to our biology. HBCUs themselves while not all needing to build hospitals should all be investing in community clinics that are connected regionally with an African American owned hospital. The pre-med and business programs should create more courses on the development of these facilities. Its impact on both wealth creation and health improvement would do wonders for African America as a whole.

It could be said that for all the benefits of the Affordable Healthcare Act proposed by President Obama, our longer term interest in building a medical ecosystem focused on the needs and issues that face the African American and African Diaspora community would go much farther in improving our health as a people. After all if health is wealth and wealth is created by ownership then we must once again build and own the ecosystem that is the DNA of our blood, sweat, and tears.

Mr. Foster is the Interim Executive Director of HBCU Endowment Foundation, Founder of the HBCU Chamber of Commerce, sits on the board of directors at the Center for HBCU Media Advocacy, & President of AK, Inc. A former banker & financial analyst who earned his bachelor’s degree in Economics & Finance from Virginia State University as well his master’s degree in Community Development & Urban Planning from Prairie View A&M University. Publishing research on the agriculture economics of food waste, full-time contributor at HBCU Money, and guest contributor for a number of African American media outlets.